Belarusian Transport: A Tale of Two Worlds — The Gap Between Urban and Non-Urban Services

Talking about public transport in Belarus, most often one imagines big cities. However, access to transport facilities, primarily to bus routes, differs dramatically depending on the size of the locality. What does the bus inequality look like for Belarusians? What role do formal service standards play in it? And what can improve the situation?

Historically, Belarusian public transport has enjoyed a fairly good reputation. Compared to that in many post-Soviet countries, in the 1990s Belarusian public transport was much less affected by spontaneous privatization and deregulation. In the 2000s, Belarus responded to the aging of its rolling stock by establishing its own manufacture of buses, trams and trolleybuses. In the 2010s, the country's expertise and independence in terms of transport facilities were enough not to copy Russia's anti-trolleybus trends. To residents of large cities, transport facilities in Belarus function if not well, then quite decently, and they do not have to adjust their daily routines to transport schedules. However, for many people living in neighborhoods outside the city center, the distance to work, to the nearest park, cinema, or good café is several kilometers. Although this limits spontaneity, it does not force one to plan the day around a bus schedule either.

The situation looks completely different when we look at Belarus from the perspective of small regional centers, agro-towns, and localities further off the Miensk Ring Road. Here, buses are often a luxury, they might not run every day, and getting to the bus stop is a real challenge, while a better job, a visit to the department store, as well as access to a wide variety of services, require going into town frequently. Walking and cycling such distances is healthy, no doubt, but appropriate infrastructure, that is, bicycle and pedestrian paths, is not always available.

Public transport is specifically intended to meet different people's needs for regular journeys at any time and at a relatively affordable price. In this text, we will try to investigate the causes of such a drastic situation with equality and justice in relation to mobility (mobility justice) in Belarus, as well as the reasons why it is hard for passengers to raise the issue with it, and what can be done.

There are various features and factors that affect public transport operation in Belarus. The relationship between managers, operators and users of passenger transport services on scheduled public transport routes is governed by a range of laws, codes, resolutions of the Council of Ministers, state standards, and resolutions of local executive committees. How these normative documents interact and whether there are contradictions between them deserves a separate publication. In this text, we will mainly focus on standards, which in practice define how long one will wait for the tram, electric bus, or trolleybus they need. The same standards determine whether it will be possible to visit one’s relatives in a rural area every day, live in an eco-friendly neighbourhood and also go to work daily by public transport.

Public Transport Standards: Just a Formality?

How can we determine who needs public transport and where? Or how frequently it should arrive, which routes it should take, and who it should serve? European countries decided to develop comprehensive Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans (SUMP) to answer these questions. Besides other types and ways of ensuring city dwellers' mobility, they outline the main provisions for public transport operation. In Belarus, plans like that were created by individual cities within the framework of joint projects with the European Union (howevere, one should bear in mind the non-binding nature of such documents and the lack of requirements to them). For example, a unified SUMP was developed for Polack and Navapolack. It was also plannedto draw up such documents for Pinsk, Bierascie, Harodnia i Orša.

A system of state social standards for servicing the country's population was developed in Belarus 20 years ago. In fact, this document outlined the bottom line for the population's living standards. This document can be referred to in communication with government agencies, but some of its provisions are written in a very simplified format and rely on clearly outdated indicators.

Inter alia, this document formalized the minimum standards of public transport services. They are shown in Table 1.

The text of the resolution of the Council of Ministers, which approved these standards, states that each of the rayon executive committees and the Miensk City Executive Committee, based on the state social standards of Belarus, shall "determine social standards for public services for administrative and territorial units (rayons, oblasts and cities of oblast subordination), taking into account their specifics and the degree of infrastructure development." Only the Miensk City Executive Committee really took advantage of this opportunity by fixing the parameters of public transport services for residents of the capital as follows [3]:

"One bus (trolleybus, tram, subway train car) operating on the line per 1.5 thousand people on weekdays;

one bus (trolleybus, tram, subway train car) operating on the line per 2 thousand people on weekends and holidays."

Bierascie [4], Viciebsk [5], Homieĺ [6], Harodnia [7], and Miensk [8] oblast committees fixed the social standards in the field of transport in their documents as they were (as in the table above). The Mahiliou Oblast Executive Committee changed only the standard for the number of passenger terminals, leaving just one bus terminal per rayon [9], otherwise regional transport standards are in line with the national one.

Thus, local authorities can significantly improve the parameters of basic public transport services for local residents with their resolutions by outlining additional basic conditions. However, the administrative staff responsible for organizing public transport operation are reluctant to use this opportunity.

The Belarusian state social standards are mandatory for organizations of all forms of ownership, and are relied on in the formation of national and local budgets, as well as state extra-budgetary funds. Thus, despite deficits in most local budgets of Belarus, spending on certain areas should not fall below the minimum to comply with the Belarusian state social standards. These are the standards set by rayon executive committees, including the Miensk City Executive Committee.

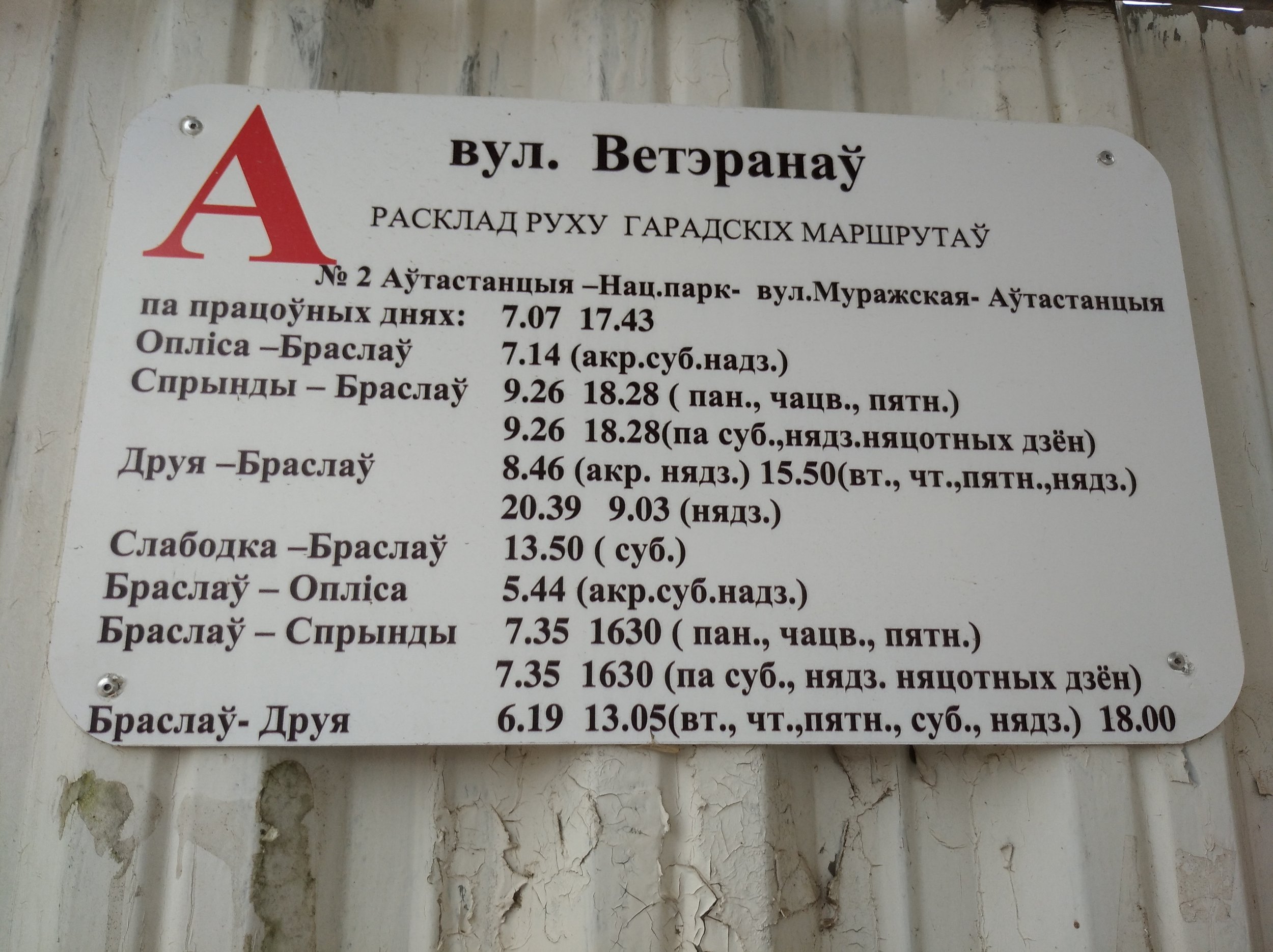

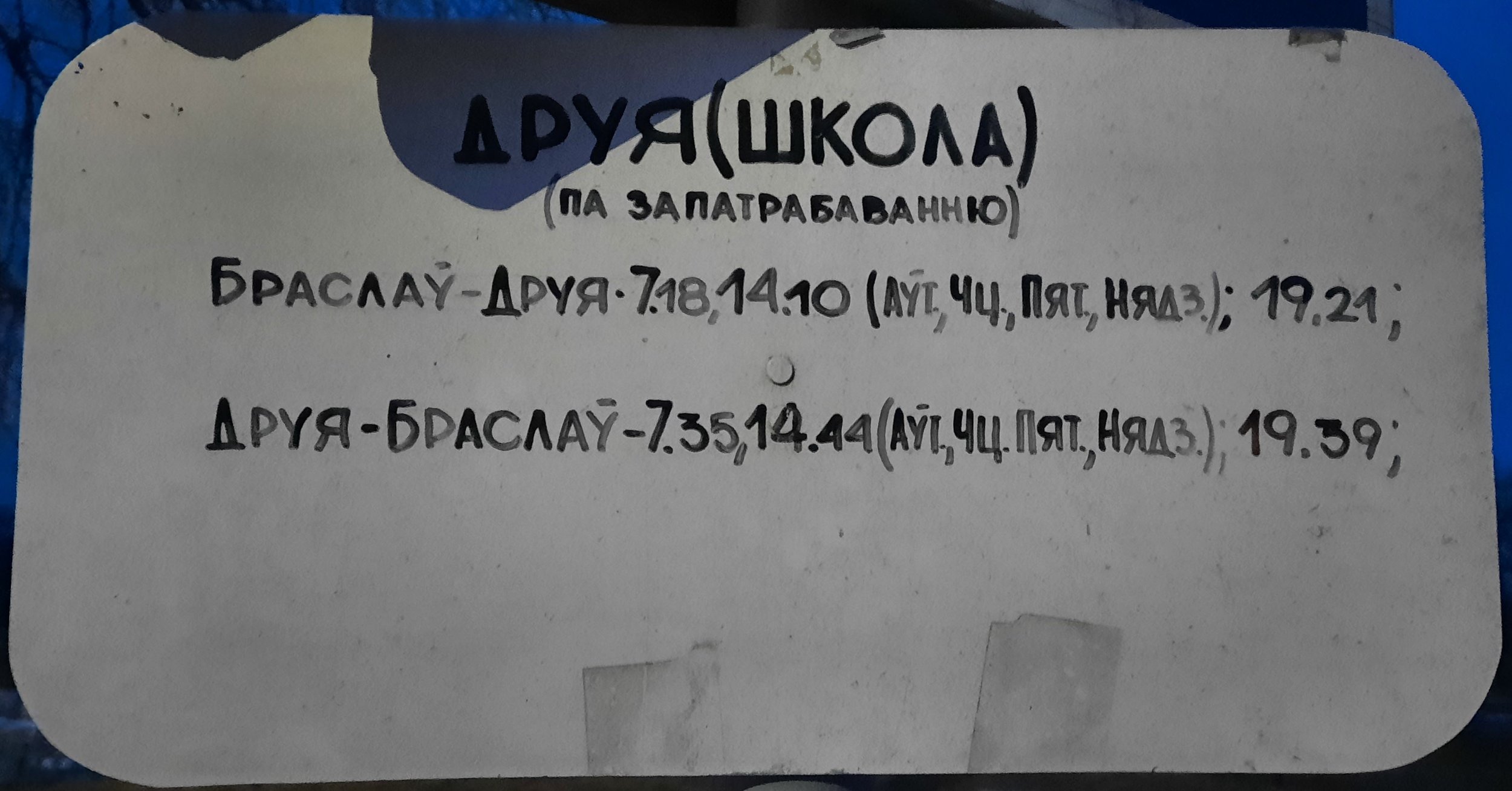

Similarly, there is nothing that may prevent the financing and parameters of transport services from being reduced to bare minimum, which, in turn, can lead to the actual disappearance of normal public transport. Such negative cases are in fact not only many non-metropolitan small towns in Russia, but also some Belarusian regional centers, for example, Miory and Šarkaŭščyna in the Viciebsk oblast, Klieck and Plieščanicy in the Minsk oblast, Pietrykaŭ i Lojeŭ in the Homiel oblast and others. There locals see buses only several times a day. Imagine that you can only take a bus to a friend's place, to work, to a store or clinic 3-5 times a day, and if you accidentally miss it, then the real alternatives are to walk, take a taxi or radically change your plans, because the next bus will only come in a few hours. And this is even though the standards described above are 100% respected there, and if you contact the local executive committee or the bus fleet, they will officially confirm this.

Bus Shortage In The "Rayons" And What To Do About It

Transport standards approved by rayon and oblast executive committees are fully respected, however, sometimes with a local touch. For example, in the Pastavy rayon of the Viciebsk oblast, buses serve some villages only on request from the village leaders to the operator of a local public transport company. If no request is made, the bus will not stop at that village. For other villages, buses run bi-weekly, not weekly, but still perform the required number of trips each month.

These standards set out indicators for the minimum number of trips to localities, depending on their population, while the time frame and days of the week are not specified. This results in situations where, depending on the decisions of transport operators (government agencies that set the public transport parameters in the oblast), residents of some small places may only have transport access on one day a week (regardless of whether it is a weekday or a weekend) and at an inconvenient time, while the transport service standard is still met, even if not all passengers manage to get on the bus that arrives on schedule.

Localities with a population of less than 20 people are not covered with transport services at all. Thus, the Council of Ministers deprives residents of sparsely populated villages and individual farms of the opportunity to receive public transport services. Obviously, the population of villages and individual farms is declining, they are located outside the main transport routes, and are not considered in the context of maintaining sustainable transport connection of their residents with the rayon's center, where the necessary social and other infrastructure is most often located. Accordingly, the state, in fact, supports the extinction of such small localities. The "ad hoc mobility" approach was developed and is used with various adjustments to provide transport services to such localities (one of the options for implementing this approach is described above and exemplified by the Pastavy rayon).

Transport services for allotment societies are not regulated by transport standards. However, in practice, housing or allotments belong to citizens, who have a more active civic position regarding the operation of public transport, so they manage to ensure a stable connection with the city by public transport all year round (but mainly on a seasonal basis). Refusals of public transport operators to regularly service the allotment societies are most often based on the absence or unsatisfactory condition of road infrastructure on the way to them: highways or roads do not always meet the standards for bus traffic, while bus stops or U-turns may be unequipped or missing. Usually, when active members of allotment societies seek solutions to issues with infrastructure, public transport coverage is resumed (if it was temporarily discontinued) or organized (if it was missing).

Developers of the standard have also determined the greatest distance that a resident of a rural settlement must overcome to gain access to public transport services. That is 3 km. If you are reading this text while being in a city, you can check out what objects are 3 km away from you to have an idea of the distance an elderly woman with a stick may have to walk. At the same time, the standard does not define how this distance should be measured: along roads, trails, or straight lines drawn between a locality or a specific house and a public transport stop. Neither is it specified with what frequency and to which destinations buses should travel from this remote stop. In practice, if there is a request formalized in appeals to government agencies from residents of such remote settlements to improve the quality of transport services, the structures responsible for the operation of public transport try to improve it, usually by extending the route scheme to the stop closest to the village.

Here is a recent case of how this can work. In the Miensk rayon, on the outskirts of the village of Ščytomiryčy, there is an allotment society called "Icarus". If it gets covered by public transport services, the situation with the latter will also improve significantly in the village, because the bus stop will be no more than 800 meters away instead of 2-3 kilometers. Residents of the village and members of the allotment society managed to steamroll construction of the stops and a U-turn for buses (although, according to the standards, all transport norms were met: there were bus stops and train stations within 3 km, both types of transport ran regularly). In January 2022, a minibus was organized to service this village, but a few days later the route was closed, as the private carrier considered it unprofitable. In October 2022 (a lot of time had passed, but people had not given up), the opening of a public transport route was announced. As a rule, such routes (run by state-owned carriers) operate for at least several months before the question is raised whether to continue their operation. As practice shows, if the route enjoys demand within the first two months (stable passenger flows appear there), it will last long. However, if the bus runs empty for months, this route can be lost for good, as our country still lacks ad hoc mobility and has not yet formalized it as a minimum standard of transport services.

The public transport standard for cities, towns and urban settlements also depends on their population. It sets out the number of buses, trolleybuses, tram and/or metro cars per certain number of residents. At the same time, this standard does not specify the time and/or days of operation, the maximum or minimum intervals between arrivals of the established number of passenger vehicles, or the minimum requirements for these vehicles. That is, to formally comply with this standard, an average town with a population of 40,000 people may provide 10 buses of any seating capacity. Furthermore, the number of trips that will (or will not) be conducted by these buses is not specified. On the ground, in a modern Belarusian city, this ensures relatively good coverage for people's transport needs during rush hours. But during off-peak hours, city transport routes either stop running or have very long intervals, which sometimes exceed one hour. In small and medium-size cities, where there are no "route taxis" either, urban mobility is not actually ensured by public transport during off-peak periods.

In localities where "route taxis'' operate, the situation might be better (with at least the latter running during off-peak hours), but mobility costs may be higher. As an example, in the town of Hlybokaje in the Viciebsk oblast, the state bus fare is set and does not depend on the day or time. But in route taxis, fare rises by around 25% in the evening on weekdays and during weekends compared to off-peak times. In large towns and cities, such vague standards cause transport services to deteriorate significantly (but not to a complete halt) outside peak hours, at night, and on weekends.

The standard for public transport services for intercity travel within oblast only requires one round trip per day. This has caused regular intercity public transport connections to disappear. Today, a significant part of the market for such transportation is actually in the hands of irregular carriers that are not controlled by anyone. This results in complete uncertainty about such trips for potential passengers. In most cases, they can travel along the intercity route they need only with the help of irregular carriers, which de-facto (according to documents) operate pre-ordered buses. Nevertheless, it is difficult to find information about such connections for those who are not aware of them or for people of age who do not use the Internet. Besides, such connections can be canceled arbitrarily (for example, if the minimum number of passengers for the trip to break even does not show up). At the same time, regular connections run only several times a day, and due to the use of small vehicles on the routes, tickets for these trips are quickly sold out.

Such a standard does an ill turn to villagers living near the main national and cross-oblast roads. They have few or no direct connections to oblast centers, so to reach them they have to travel via another rayon center (which takes almost a whole day). Or they can take a private bus, paying the full fare for travelling between bigger towns, and not a cheaper cost from their village to the town in the rayon or oblast they need. Using the example of settlements in the Miensk oblast from this text on the mlyn.by online portal, one can see how such a system of standards works in practice

"Stopover" Standards

One of the elements of traveling by public transport is waiting for it. The system of state standards does not regulate the conditions in which one is expected to wait. The waiting conditions (the setup of public transport stops) are regulated by technical documentation focused on the process of creating a stop and its setup, which has very little to do with the needs of passengers who use this infrastructure. The availability of stops is also essential when communicating with government agencies regarding the introduction of new routes.

The minimum requirements for the setup of stops are indicated in the technical documentation for the construction and maintenance of roads and streets. Therefore, bus stops on motorways [10] are to have the following features: a platform where public transport can stop and let passengers on; seats; a rubbish bin; shelters or places where passengers can hide in poor weather conditions; information about the stop name; and devices for displaying bus timetables.

The transport stop setup requirements are almost the same in all localities, except that the availability of spaces where passengers can take shelter from the rain (the so-called pavilions) is not specifically regulated.

Thus, if any of the listed elements are missing at the transport stop next to you, feel free to draw the attention of government agencies to this through appeals or calls to responsible persons, and the situation will be improved. Sadly, technical documentation does not contain any more information on the stop equipment. For instance, an electronic scoreboard is needed with live public transport updates, but the platform specifications for public transport stops and passenger boarding are not clearly defined in the regulations. Such a boarding platform can be just a concrete slab installed on the side of the road. With certain persistence from potential passengers, it can be "built" fairly quickly (it will take more time to coordinate the location of the stop with the traffic police). Therefore, if they respond to your appeal by saying that the route to your place cannot be organized, since there are no stops, you can easily offer a concrete slab as an option.

It is noteworthy that the requirements for the outlook of pavilions are not fixed in the technical documentation, so in fact any structure with a roof and a bench next to it (not necessarily under the roof) can be considered a pavilion. In bad weather, this often creates problems, because the most common type of pavilions can only hide you from vertical rain without wind, and its dimensions (which are not regulated either) may not be enough to accommodate all passengers.

What should be the distance between stops and why should passengers care?

The requirements [11] for transport stops in populated areas specify the distance between stops (from 350 to 600 m for buses, trolleybuses, trams, from 800 m to 1.2 km for high-speed buses and trams).

The "Rules for the carriage of passengers by road" [12] set out the requirements towards distance between stops as follows (quotes):

"Buses in regular traffic should transport urban passengers between the main points of origin and have intermediate stops, usually 350-800 m apart in areas with multi-storey buildings and 500-1000 m apart in areas with low-rise buildings."

"Buses in regular traffic should transport suburban passengers between the main points of departure and arrival (such as suburban areas, recreational zones, urban settlements, and rural centers), and the distance between stops on these routes should be at most 6000 m (in residential areas) and at least 1500 m (for new routes)".

This is not bad: the more frequent the stops, the slower the speed of public transport in the city, and, accordingly, the more time you will spend in transit. The downside of this approach may be an increase in walking time to stops, but due to building regulations (which are discussed below), construction and transport experts are trying to find an adequate balance between walking distance to each stop and the distance between stops.

In suburban areas the situation is more complicated. Here, the distance between stops is fixed in the range from 1.5 to 6 km. This norm allows design institutions, in consultation with transport specialists (if they are not diligent enough), to cut costs on building stops, which results in three-kilometer walks from villages to the closest stops on highways. It is not required explicitly, for instance, to construct a footpath from the village to the stop, forcing people to walk on the road with cars in any weather and at any time.

How far will the stop be from the entrance to your house?

Imagine a situation: you have decided to invest in construction or purchase an apartment in a newly built house in one of the young neighborhoods, in a quiet place next to a forest on the city’s outskirts. You pay a large sum in dollars, invest in refurbishing, settle in, and are planning the travel time to work by public transport. So where can the closest stop be possibly located?

Construction regulations [13] set out the following requirements:

in the case of suburban passenger transport, the walking distance to them should be no more than 1 km;

for low-speed types of passenger transport, the walking distance to the nearest stop is shown in Table 2;

the walking distance to metro stations and high-speed tram stops should range from 600 to 800 m.

If your apartment is in a block of flats in the center of a large city, the walk from your block to the nearest stop will take no more than 10 minutes. However, if you live in a block of flats from the Khrushchev era or in a pleasant old two-story house, you will have to walk 10 to15 minutes. If you reside in an estate of your own in the village, the walk may take up to half an hour.

It is usually hard to change this walking distance and time in cities, if it is in line with the regulations. In rural areas, where there are only a couple of stops in the whole village, with some perseverance in communication with government agencies, it is quite possible to wrest out the construction of additional stops, although this might not be quick. The question concerning measuring distance by air or by trails is also relevant for these standards.

What Can Be Improved In The First Place?

What came to the forefront when we analyzed the formal transport service standards in Belarus outside large cities? First of all, it was the uneven distribution of access to transport services. Thus, small localities are disproportionately deprived of public transport. More often than not, social groups with the least access to public transport include elderly, low-income, and socially vulnerable people.

Transport service standards are designed to minimize, even theoretically, the accountability of transport service providers at the local level. However, this is also the level where complaints are directed, and complaints are one of the traditional and few remaining ways to influence the quality of transport services in Belarus. Figures in the standards are often unspecific and vague, that is, they are neither validated by demand studies, nor in line with the views of the expert community on the minimum necessary transport accessibility and population mobility.

The quality parameters for transport services like the frequency of departures during the day or week, waiting time for a tram/trolleybus/electric bus/bus, or the seating rate for public transport vehicles are not specified in the standards and norms. In the current management of this sector, this implies that public institutions may not care about the comfort of traveling by public transport (as they have no duty to), as long as passengers stay passive. Therefore, until comprehensive mobility documents are developed as a standard in the country, the existing documents need to be updated and made adequate. This can be done through personal communication with the management and active specialists of public transport organizations, correspondence with the administrations of rural councils, city, rayon and oblast executive committees, as well as with the help of media coverage. Appeals and complaints also work.

What, in our opinion, could be the first steps on the part of transport workers, executive committee administrations, and scientists in the field of transport mobility in Belarus?

This could be an aggregated document that would contain all existing standards and regulations in the field of public transport with indicators adequate to the modern world.

Alternatively,

The oblast, rayon and Miensk city executive committees, along with regular passenger transport operators, could review the social standards for transport (and define the quality parameters for transport services) and specify the following aspects of public transport operation in the standards:

the start and end time for provision of public transport services in localities that are subject to administrations of regional executive committees (Miensk City Executive Committee);

provision of public transport services at night, on holidays and days preceding them;

the maximum allowable interval for public transport during peak and off-peak hours, as well as on weekends;

recommendations on the choice of the type of public transport in the design of new neighborhoods, industrial enterprises, and public facilities (large shopping malls, cinemas, parks, etc.);

the permissible or maximum seating rate for buses, trolleybuses, trams (based on research, in modern public transport it should not exceed 3 persons per square meter of vacant floor space);

minimum technical requirements for equipment (for example, the number of doors, air conditioning, etc.), color and design, accessibility of public transport vehicles and transport infrastructure facilities;

the necessary requirements for equipment and location of stops for certain areas;

within the coverage area of all rural settlements, regardless of the number of inhabitants in them, with account of interests of low-mobility categories of citizens, the distance to stops shall not exceed 1.5 km;

other aspects of public transport that stem from the peculiarities of the region's socio-economic development.

At the same time , it is fundamentally important that the figures and indicators in the norms are based on the needs of people, and not on the desire of responsible officials at different levels to enjoy trouble-free reporting without much effort. If it is impossible to conduct empirical demand studies in the field, it is possible to resort to international standards, as well as the best practices of those countries and localities that are recognized as the most comfortable for life according to structured estimates.

If you want to explore the topic further, you can read these documents on your own (available in Russian):

Appendix to Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus No. 724 dated 05.30.2003 (amended by Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus No. 720 dated 12.14.2020) "On measures to implement a system of state social standards for servicing the population of the Republic of Belarus", paras 25-30: https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=C20300724https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=C20300724 .

Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus No. 972 dated 30.06.2008 (as amended by Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus No. 636 dated 08.31.2018) "Rules for passenger road transportation": https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=C20800972/https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=C20800972 .

Resolution of the Miensk City Executive Committee No. 1013 of June 26, 2003 "On establishing a list of state social standards for servicing the population of the city of Miensk" (as amended by the Resolution of the Minsk City Executive Committee No. 795 dated March 11, 2021 (National Legal Internet Portal of the Republic of Belarus, 04.07.2021, 9/107945): https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r90301013/https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r90301013 .

Resolution of the Bierascie Oblast Executive Committee No. 179 dated March 25, 2021 "On the list of state social standards for servicing the population of the Bierascie oblast": https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r921b0108233.

Resolution of the Viсiebsk Oblast Executive Committee No. 464 dated July 25, 2011 "On the list of state social standards for servicing the population of the Viciebsk oblast": https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r911v0043093.

Resolution of the Homiel Oblast Executive Committee No. 973 dated October 20, 2017 "On the list of state social standards for servicing the population of the Homiel oblast": https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r918g0087411.

Resolution of the Harodnia Oblast Executive Committee No. 156 dated March 29, 2021 "On the list of state social standards for servicing the population of the Harodnia oblast": https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r921r0108186.

Resolution of the Miensk Oblast Executive Committee No. 486 dated June 30, 2003 "On establishing a list of State social standards for servicing the population of the Miensk oblast": https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r903n0486.

Resolution of the Mogilev Oblast Executive Committee dated July 23, 2007 No. 15-25 "On the list of state social standards for servicing the population of the Mogilev oblast" [electronic resource]: https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r921r0108186https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=r921r0108186 .

Technical Code of Established Practice ТКП 45-3.03-19-2006 (02250) "Automobile roads. Design standards", p. 10. – Introduction. 01.07.2006. - State Committee for Standardization of the Republic of Belarus, 2006.

Technical Code of Established Practice ТКП 45-3. 03-227-2010 (02250) " Streets of settlements. Building design standards", pp. 6.1, 13.14. – Miensk: Ministry of Architecture and Construction of the Republic of Belarus, 2011. – 46 p.

Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Belarus No. 972 dated June 30, 2008 "On certain issues of passenger transportation by road", pp. 80, 85: https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=c20800972

Resolution of the Ministry of Architecture and Construction of the Republic of Belarus No. 94 dated November 27, 2020 "On approval and enactment of building regulations CH 3.01.03-2020", pp 11.2.3, 11.5.3: https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=w22136480p&qid=4671524https://etalonline.by/document/?regnum=w22136480p&qid=4671524